Planning Your Climate-Adapted Native Plant Garden: A Comprehensive Guide for Sustainable Success

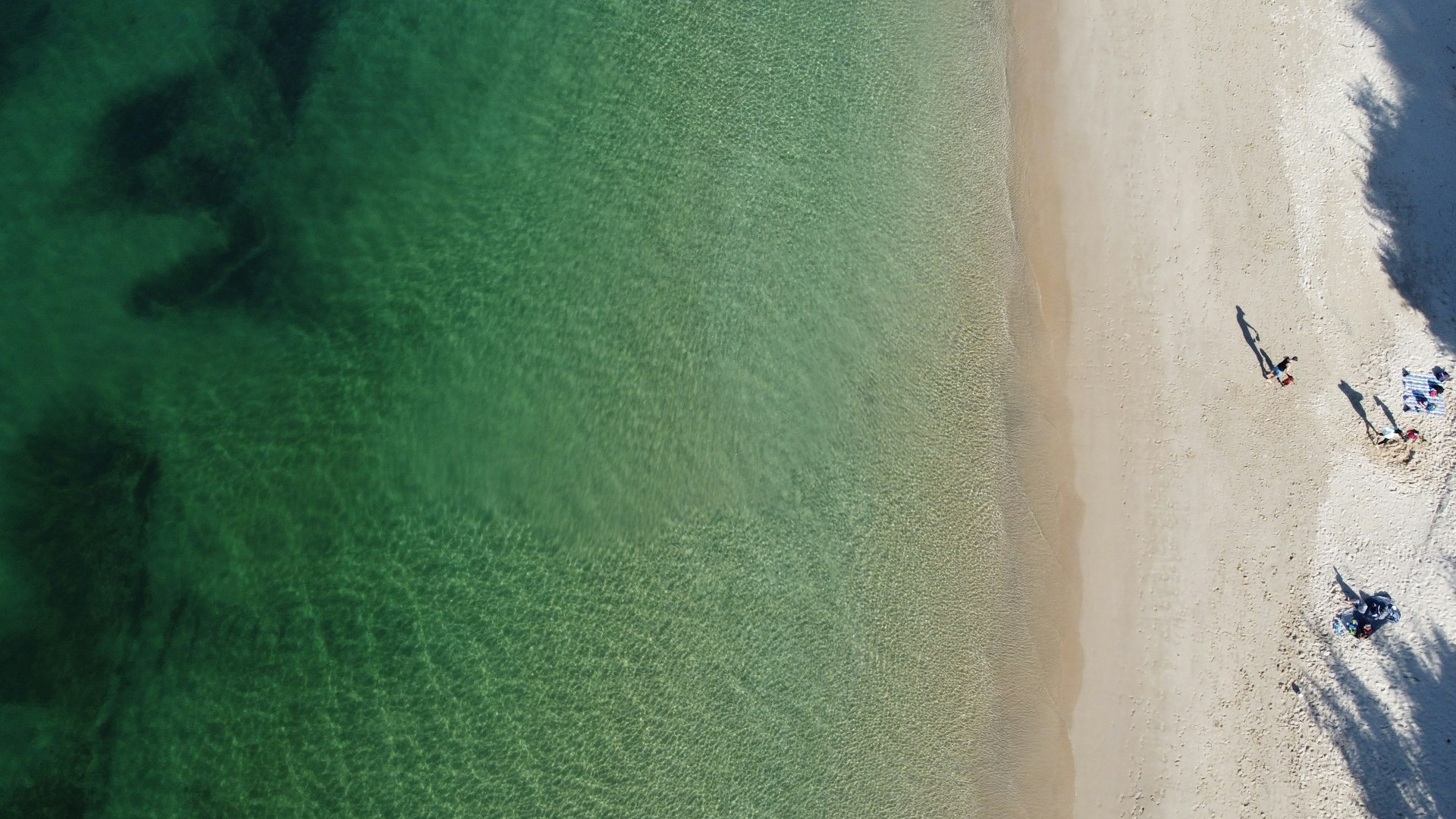

Photo by Hanna Haag on Unsplash

Introduction: The Value of Climate-Adapted Native Plant Gardens

Creating a climate-adapted native plant garden is an increasingly popular approach for homeowners and land managers seeking resilient, sustainable landscapes. By selecting plants naturally suited to your region’s current and future climate, you promote biodiversity, reduce maintenance, and support local wildlife. This guide provides a step-by-step approach to planning, implementing, and maintaining a thriving climate-adapted native garden, drawing from verified expert sources and practical examples.

Understanding Climate-Adapted Native Planting

Climate-adapted native plant gardening focuses on selecting species that are indigenous to your area and suited to both current and projected climate conditions, including shifts in hardiness zones and precipitation patterns. Native plants require less water, fertilizer, and pest control, making them an eco-friendly choice for sustainable gardening. According to Northeast conservationists, native gardens provide 50% higher abundance of native birds, three times more butterfly species, and double the abundance of native bees compared to non-native plantings [1] .

Step 1: Site Assessment and Planning

Begin by thoroughly assessing your garden space. Define the area for the planting project-whether it’s a series of pots, a narrow strip, or an entire yard. Observe the light conditions throughout the day, noting areas of full sun, part shade, or deep shade. Identify microclimates, such as wet spots or wind-exposed zones, and divide your site into smaller zones with similar conditions [2] . Inventory your existing landscape for sun and shade patterns, moisture accumulation, and accessibility from your home [5] . These observations will help you select plants that are most likely to thrive.

Step 2: Selecting Climate-Adapted Native Species

Choose plant species that are native to your region and suited to your site’s microclimates. Consult official hardiness zone maps and local extension resources to identify species adapted to both current and anticipated climate conditions

[3]

. For example, in the Northeast, species like hophornbeam (

Ostrya virginiana

), Kentucky coffeetree (

Gymnocladus dioica

), and serviceberry (

Amelanchier canadensis

) are recommended for their adaptability and ecological value. In the mid-Atlantic, white oak (

Quercus alba

) and swamp willow (

Salix nigra

) provide habitat for local insects and support pollinators

[4]

. If you live in Colorado or the Front Range, low-water native plants can be integrated into non-irrigated pockets to conserve water and prevent the introduction of noxious weeds

[5]

.

Photo by Sveta R on Unsplash

Step 3: Designing for Function and Aesthetics

Plan your native garden to fulfill specific functions, such as creating shady refuges, sunny pollinator patches, privacy hedgerows, or colorful borders. Native grasses, flowering plants, shrubs, and trees can be combined to provide year-round interest, food sources for wildlife, and improved garden aesthetics. For shady areas, select species adapted to low light, like striped maple (

Acer pensylvanicum

). For sunny spots, drought-tolerant flowering plants attract bees and butterflies. Shrubs such as American hazelnut (

Corylus americana

) and Toyon (

Heteromeles arbutifolia

) can serve as beautiful, ecologically beneficial alternatives to conventional fencing

[2]

.

Step 4: Implementation-Preparing and Planting

Once your design is finalized, prepare the soil by removing invasive or non-native species that compete with natives and may harm local ecosystems [1] . Amend soil as needed based on the requirements of your chosen plants. Group plants by their light and moisture needs to maximize survival and minimize maintenance. Plant in spring or fall, when temperatures are moderate and rainfall is more reliable, to reduce transplant shock and water needs. Mulch around new plantings to retain soil moisture and suppress weeds.

Step 5: Maintenance, Monitoring, and Adaptation

Native plant gardens generally require less maintenance than conventional landscapes, but some care is still needed. Water new plantings regularly until established, then gradually reduce supplemental watering. Monitor for pests, diseases, and invasive weeds. Prune shrubs and trees as needed to maintain shape and encourage healthy growth. As climate conditions shift, observe plant performance and replace struggling specimens with better-adapted choices. Routine inventory and adaptation help ensure your garden remains resilient and beneficial over time [3] .

Accessing Resources, Services, and Expert Guidance

To access reliable plant lists and design inspiration, consider consulting local conservation organizations, university extension offices, and native plant societies. For North America, the Native Plant Societies often host plant sales, workshops, and online guides. The U.S. Department of Agriculture and state extension services provide hardiness zone maps and planting advice. If seeking professional design assistance, contact local landscape architects or nurseries specializing in native plants. When in doubt about plant suitability, search for “[your region] native plant list” or contact your county extension office for personalized recommendations.

Potential Challenges and Solutions

While climate-adapted native gardening offers many benefits, challenges can arise. Some native species may not be readily available in local nurseries; consider ordering from reputable native plant suppliers or participating in regional plant exchanges. If dealing with poor soil, amend with compost or select species adapted to low-nutrient conditions. In areas with frequent droughts, prioritize drought-tolerant natives and use drip irrigation to conserve water. To manage invasive species, stay informed about local noxious weed regulations and remove problem plants promptly. Collaboration with neighbors and community groups can amplify positive impacts and create larger, contiguous habitats for wildlife.

Alternative Approaches and Phased Implementation

If budget or time constraints exist, implement your native garden in phases. Start with a small pocket garden or replace a single bed with natives, then expand as resources allow. Container gardening offers flexibility for renters or those with limited space. Mixed landscapes, featuring both native and climate-adapted non-native species, can be effective, provided all plants are non-invasive and suited to local conditions [5] .

Key Takeaways

Climate-adapted native plant garden planning delivers substantial ecological and aesthetic rewards. By following a systematic approach-site assessment, species selection, functional design, careful implementation, and adaptive maintenance-you can create a vibrant, resilient garden that supports biodiversity and withstands changing climate conditions. For further guidance, consult your local extension service or native plant society, and leverage authoritative guides for ongoing education and support.

References

- [1] University of Massachusetts (2020). Northeast Conservationists Offer Climate-Smart Garden Guide Highlighting Native New England Species.

- [2] California Native Plant Society (2022). Create a Native Plant Garden: Sample Designs and Tips.

- [3] NE CASC, USGS (2021). Gardening with Climate-Smart Native Plants in the Northeast.

- [4] The Nature Conservancy (2023). Native Plants Garden Guide for the Chesapeake Bay Region.

- [5] Colorado State University Extension (2018). Low-Water Native Plants for Colorado Gardens.